Early Childhood Development (ECD) – Survey and Infrastructure Support

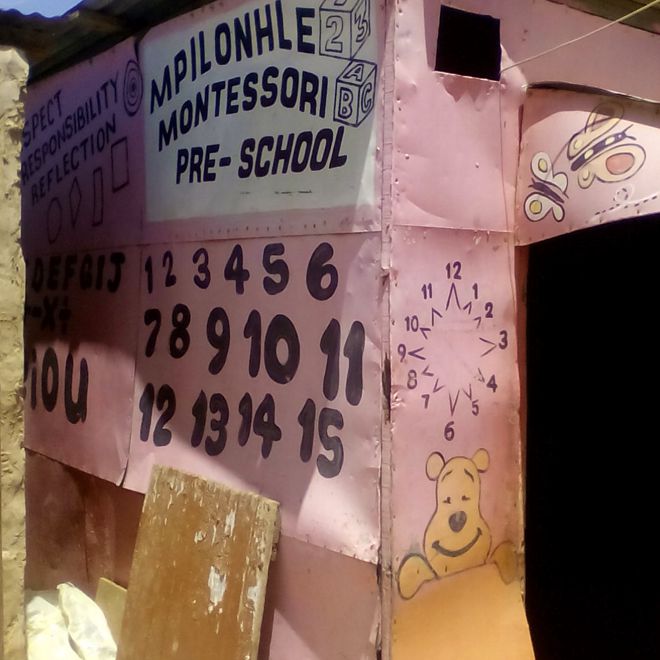

Large numbers of children in underserviced communities lack access to acceptable ECD care and services. They also often face a range of health and safety threats. Many centres are not yet registered and thus fall outside of the system of registration and related state oversight and support. Since 2013, PPT has therefore collaboratively developed a programmatic ECD response model. PPT also assists ECD transformation in S.A. by supporting municipalities, undertaking field surveys and planning appropriate infrastructure improvements.

ECD Video

Improving access to adequate ECD services is recognized as a national priority (e.g. within the National Development Plan and by key Departments such as Social Development). ECD is recognised as being in a state of crisis.

Since 2013, PPT has played a significant role in developing, piloting, refining and mainstreaming a more programmatic and inclusive ECD response model for South Africa. Through its work at grassroots level over many years, PPT identified the existence of large numbers of un-registered, under-resourced ECD centres (‘creches’) in informal settlements and other under-serviced communities as a strategic priority which were not receiving sufficient attention. Click here for a report on ECD centres in informal settlements compiled with the assistance of the Housing Development Agency (HDA), 2014.

PPT has therefore worked systematically and collaboratively with multiple stakeholders since 2015 towards an improved ECD response model which achieves better population coverage (reaching and supporting optimisinglimited fiscal and other resources). Key principles and elements of the emerging response model include:

- Responding programmatically – i.e.: at scale and in a structured fashion instead of reactively and on an ad hoc basis; allocating limited fiscal and other resources as efficiently as possible based on proper information and strategies so as to achieve optimal outcomes.

- Prioritising unregistered and under-resourced ECD facilities as the main priority for support and improvement because this is where most vulnerable children are and because improving existing facilities is much more cost-effective than building new ones.

- Identifying all existing facilities, including unregistered ones, in order to better understand the status quo and to enable appropriate population based planning (this identification and database establishment can be achieved by obtaining existing databases, app-based or desktop searches and ECD field surveys).

- Improving ECD infrastructure (mainly by improving existing facilities and, where necessary, by also building appropriate/affordable new ones) so as to meet minimum DSD norms and standards and enable registration with the DSD. Most ECD centres in low income communities are heavily under-resourced and inadequate infrastructure is typically the biggest barrier to registration and inclusion.

- Proactively registering ECD centres utilising the DSD’s new incremental conditional registration framework (gold-silver-bronze – with flexibility on minimum norms and standards at the latter two levels.

- Developing and adopting municipal ECD strategies and sector plans in order to establish practical and clearly defined approaches and to enable improved multi-stakeholder coordination and optimised roles and resource use.

- Embracing informality and being flexible in terms of statutory and regulatory requirements e.g. in terms of the requirement for approved building plans, formal zoning and land use approvals, non-essential infrastructure requirements etc. The new incremental ECD registration framework already lays a platform for this.

- Increasing fiscal allocations to ECD as the programmatic delivery model kicks in and is able to channel and utilise resources more effectively. There is currently insufficient funding in the system to meet the needs on both the capital/infrastructure and ECD grant/operational sides.

PPT’s ECD work dating back to 2013 has involved multiple collaborations and initiatives with a focus on action research, pilot projects, field surveys, infrastructure planning, developing standard infrastructure typologies, developing guides and policies etc.

Click here for diagram of programmatic ECD response model.

Based on PPT’s ECD work to date including data obtained from extensive ECD field surveys and related data analysis of 1114 centres in 8 municipalities serving 41,419 children and infrastructure improvements undertaken in 5 municipalities, the following are amongst the most key findings:

- Almost two thirds (64%) of the ECD centres were not registered;

- 75% of the ECD centres and children did not benefit from DSD ECD subsidies;

- A third (33%) of the ECD Centers were not known by government (DSD or Municipality)

- 57% of the ECD centres were registered NPOs;

- Almost half (49%) of the centres are NPO owned/managed and 46% by private individuals. This can be a constraint for state investment. Such centres may only be eligible for basic services improvements (e.g. water, sanitation, storm water management, fencing and outdoor equipment)

- More than half (52%) of the ECD services were rendered from dedicated centres and 40% from private residences;

- Most centres surveyed are relatively small – The average size was 37 children.

- Most centres were well established: Almost half the centres (45%) have been operational for > 10 years and 21% for between 5 and 10 years;

- Most centres have potential to improve and are viable for support. Despite their limited resources, 62% of the centres show commitment under difficult circumstances and have potential to improve, provided they receive support

- Three quarters (75%) of the ECD centres operate within formal buildings.

- Low-income levels are a key constraint: Two thirds (67%) of the ECD centres collect an income of R0-150 per toddler per month . This places centres under extreme financial pressure. Even when the per child subsidies (R17 per child per day) are provided, funding is still insufficient to meet bylaw requirements e.g. toilets, fencing, floor space etc.

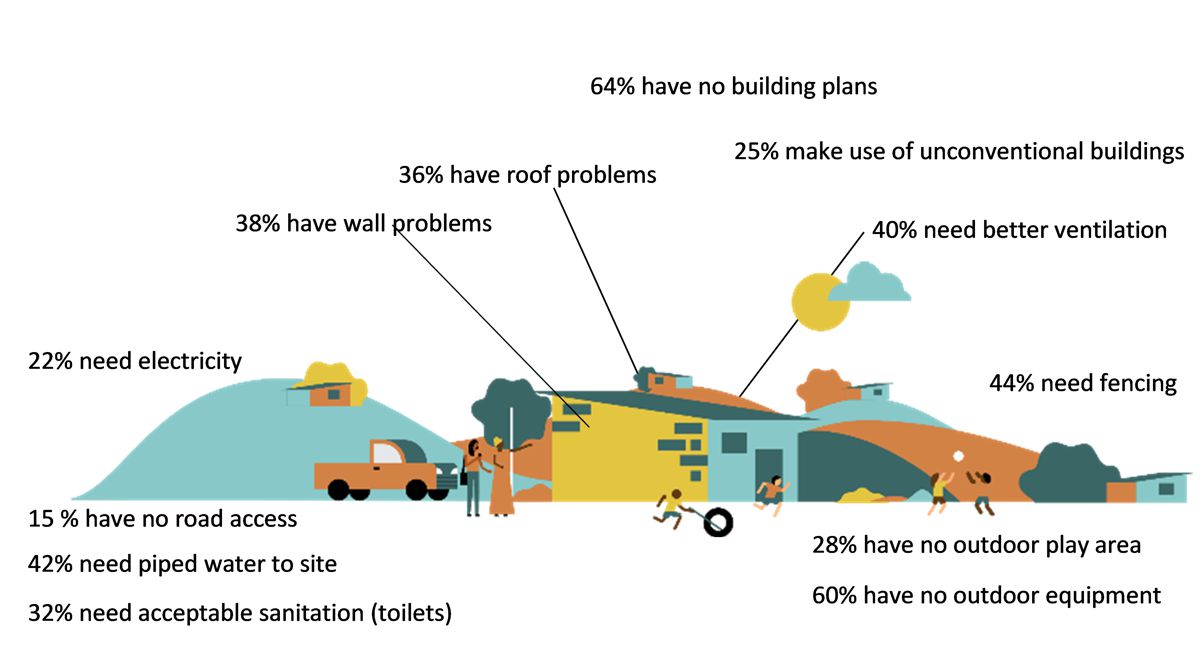

- Infrastructure deficiencies pose the most significant barrier to centre improvement and registration. 88% of ECD centres surveyed reported infrastructure deficiencies i.e. basic services, building, accommodation or site issues and require infrastructure improvements. These deficiencies pose problems in respect of health and safety of children as well as meeting norms and standards for partial care registration with the Department of Social Development.

- Municipalities have limited access to capital funding. ECD is therefore regarded as an unfunded mandate. It is imperative that the municipality and DSD prioritise those centres and operators that show most potential to provide acceptable ECD services and are suitable for state investment (not all centres are).

- Improvements to existing facilities are far more cost-effective than new builds. Approximately 4 to 5 times more of children can be assisted with infrastructure improvements than for equivalent capital investment in new builds. Many municipalities prefer new builds but there is insufficient budget available through the fiscus to address the entire national ECD services backlog by means of building new ECD facilities. An appropriate mix of improvements and new builds.

- ECD is often not provided for in the municipal Integrated Development Plan (IDP) as required in the National Integrated ECD policy (2015). Few municipalities plan and budget for ECD infrastructure improvements and new builds.

- There is little area-level data available on local demand for ECD services. Neither the DSD nor municipalities have this data. Population based planning is important to create expanded access to ECD services. ECD surveys help provide some of this data.

- Municipal ECD roles are often not clearly understood. Municipalities have an important role to play in ECD. However, their role is poorly defined from a developmental (as opposed to regulatory) point of view.

- Registration flexibility is essential. ECD centres in low income and underserviced areas are unable to meet the environmental health, child care norms and standards and are therefore unable to obtain partial care registration with DSD. The newly developed incremental and more inclusive ECD Registration Framework is expected to provide the necessary flexibility and enable ECD centres to incrementally meet norms and standards and obtain conditional registration (bronze or silver) and eventually full (gold) registration.

- Rigid land use requirements, land rights issues and related costs also pose a barrier to registration. ECD centres in low income areas cannot afford the appointment of a professional town planner and the cumulative cost of rezoning, consent use, departures, building plan approval and the cost of adhering to conditions set by the municipality. ECD centres in informal settlements are unable to secure land use rights in the absence of town planning schemes, zoning etc. These are issues ECD centres cannot control. Municipalities are generally not managing informality well and ECD centres in informal settlements have no choice to but to operate their centres illegally. Land use matters are currently investigated to see how best municipalities can play a more enabling role.

There is generally weak co-ordination for ECD support and infrastructure investments: There needs to be stronger co-ordination, planning and prioritisation between Municipalities and the DSD, but also with local support NGOs. Multi stakeholder ECD Project Steering Committees were established in all municipalities. Such committee work best in municipalities where there is some political support for the roll out of ECD programmes. The eThekwini ECD PSC is a good example.

Key ECD partners since 2013 have included, amongst others: the Departments of Social Development (DSD), Human Settlements (DHS), Planning Monitoring and Evaluation (DPME, Cooperative Government and Traditional Affairs(COGTA)); the Programme to Support Pro-Poor Policy Development in S.A. (PSPPD) via the DPME; eThekwini Metro; five KZN Local Municipalities; two Eastern Cape Local Municipalities; the University of KwaZulu Natal (UKZN); Nelson Mandela Foundation; Training and Resources in Early Childhood Development (TREE); Ilifa Labantwana; Network Action Group (now Impande); LIMA Rural Foundation; Assupol Community Trust; Angela Mai (funder); Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR).

Partners

Departments

Funders

The following are some of the key challenges and problems facing ECD in South Africa which have informed PPT’s commitment to developing a more appropriate ECD response model and making ECD support a priority PPT programme. A paradigm shift and new programmatic approach are urgently required to create hope for young children from poor households and to break long-term cycles of poverty.

- At least 2 million children are cared for in under-resourced and/or unregistered ECD centres in S.A.

- Approximately1 million children in South Africa aged 3-5 years do not have access to any form of early learning programme;

- Approximately 4.5 million children under six years of age live in poor households (SAECR 2019) of which approximately 2.3 million attend some type of group learning programme;

- Most ECD centres have been established by community based organisations, not-for-profit organisations or micro-enterprises in the absence of state support;

- Infrastructure is the most important barrier to registration and many children face health and safety threats;

- The Children’s Act requires all ECD centres to register as partial care facilities;

- Many ECD centres are not registered with the Department of Social Development (DSD) as they are unable to meet infrastructural, health and safety norms and standard with their limited Income (R50 – R250 per child per month)

- Without registration, centres are unable to access much-needed state support (including DSD operational subsidies and training) and they remain outside the system and ‘off the radar’ of government and children remain vulnerable;

There has been a general lack of data, effective municipal-level ECD response plans (i.e. population based plan), limited communication regarding ECD policy and limited effective cooperation and coordination between municipalities, COGTA, the DSD and DOH, support NGOs and other stakeholders, etc.

This video was made by Ilifa Labantwana on typical centre improvements required at Inkhanyezi ECD centre in Amaoti, eThekwini.

In 2015 PPT embarked on a collaborative action research in order to develop an ECD survey, categorisation and infrastructure support model. This included amongst other things: field survey tools, a categorisation framework, infrastructure designs, norms and standards, as well as a funding model.

Funding was secured from the EU via the Presidential Programme for Pro-Poor Policy Development (PSPPD) which was administered by the Department of Planning Monitoring and Evaluation. The project was undertaken in collaboration with University of KwaZulu Natal (UKZN) and Training and Resources in Early Childhood Development (TREE) as well as the eThekwini Metro and Department of Social Development.

The research title was “A new area based approach for improved and up-scaled ECD services for the urban poor”. The study area was within Amaoti, a large informal settlement in the north of eThekwini. The response model tested, consisted of two main elements: a) an ECD Rapid Assessment and Categorisation (RAC) method (including a field survey); b) incremental ECD development plans and related response packages. The project included focus group discussions with ECD practitioners and parents, the training of 14 practitioners from the prioritised centres and the issuing of educational equipment to prioritised ECD centres. Click here to open the ECD policy brief: Scale-able ECD Response Model, 2017.

The action research initiative provided significant new information and learning pertaining to ECD in informal settlements that contributed to the refinement of the Response model. The research clearly demonstrated the need for a programmatic response, proved the efficacy of the new Response Model, highlighted the preconditions for replication and upscaling of ECD services to poor communities and provided evidence for policy development.

Click here for link to the Synthesis Report on “Informal Early Childhood Development Centres -a new area-based approach for improved and up-scaled ECD services for the urban poor.” Click here for the full report on the PSPPD ECD Action Research (2017).

Research findings were presented to the PSPPD II Research Conference on Research findings and potential policy implications held in March 2017 (Click here for presentation) as well as at a multi-stakeholder Research Dissemination Conference organized by the Premiers office in KZN (Click here for presentation).

In 2015 PPT started collaborating with Ilifa Labantwana in respect of developing and piloting an ECD survey and infrastructure response model which occurred in parallel with the afore-mentioned PSPPD ECD action research project. The main focus was on:

- Identifying, surveying and mapping existing ECD facilities (mainly in under-resourced low income communities).

- Developing an ECD database with detailed information on ECD centres.

- Categorising and prioritising centres for potential infrastructure improvements.

- Assessing infrastructure adequacy and needs at selected ECD facilities.

- Developing ECD infrastructure improvement plans and cost estimates.

- Supporting the development of more effective ECD coordinating structures at municipal level

- Developing ECD tools and methods.

- Developing a comprehensive Municipal ECD Guide and proforma Municipal ECD Strategy.

- Working with COGTA to ensure the inclusion of ECD in municipal IDPs.

Click here for the SEIS infographic and click here for the SEIS presentation.

The programme started in KZN but grew as it progressed to include municipalities in the Eastern Cape. The collaborating partners also expanded to include, for example, KZN COGTA, Assupol Community Trust, Network Action Group, and Cookhouse Windfarm.

During the course of the programme, PPT worked with and provided support to the following municipalities:

- 7 Local Municipalities: Five LMs (Umzumbe, Umdoni, Umvoti, Msinga and Nquthu) in KwaZulu Natal (KZNN) and two LMs (Blue Crane Route and Raymond Mhlaba) in the Eastern Cape(EC)

- Four District Municipalities: Two DMs (Umzinyathi DM and Ugu DM) in KZN and two DMs (Amathola DM and Sarah Baartman DM) in the EC.

- the eThekwini Metro.

All municipal ECD infrastructure support commenced with a) raising municipal awareness with regard to ECD being declared a national priority; b) the unpacking of roles and responsibilities of municipalities as set out in the National Integrated ECD Policy and c) the establishment of multi-stakeholder coordination structures to guide and oversee the implementation of the ECD infrastructure response model at municipal level.

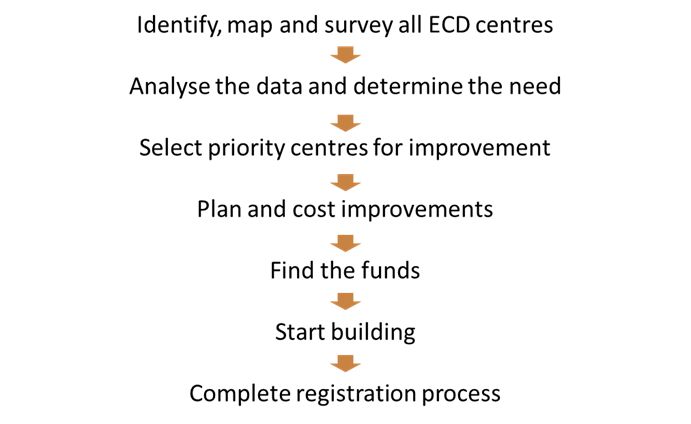

The ECD process at municipal level can be summarised as follows:

This strategic infrastructure approach requires a radical mind-shift for municipalities – moving from compliance mode to the adoption of a developmental approach.

eThekwini formally adopted and allocated funding to the ECD infrastructure support programme in 2017/18 and entered into a MOA with PPT to assist with the upscaling of ECD surveys in underserviced areas, the preparation of project pipelines and the drafting of a ECD strategy for the city. EThekwini embarked on the improvements of the first 14 ECD centres procuring small contractors via formal quotation procurement systems. This process is rather slow and requires a lot of manpower. A more streamlined procurement process is currently investigated.

Click on each of the items to open:

- Potential scope of work for ECD infrastructural improvements

- Overview of ECD infrastructure response typologies

- Photos of ECD centre improvements

- Close out report – Phase 1 Msinga and Nquthu infrastructure improvement

- Amaoti video on infrastructure improvements

- A case study Khulisisiwe Umlazi (2019)

- eThekwini Briefing PowerPoint (2021)

- Costing of centres – per investment level per municipality (2017)

Most of the local municipalities agreed to and valued the process i.e. working collaboratively with stakeholders, area based surveys and the preparation of project pipelines for inclusion in IDPs, but most were unable to allocate budgets for implementation. Municipalities insisted that government will have to ring fence additional funding within existing funding mechanisms (e.g. MIG or USDG) to enable Municipalities to adequately budget for the rollout of the ECD infrastructure support programme. However, Nquthu and Msinga managed to allocate budgets in the following year for a few new builds.

It was also encouraging to see that funders adopted the ECD infrastructure response model. Assupol Community Trust funded the improvements of a total of 40 ECD centres in Nquthu and Msinga (KZN) while Cookhouse Wind Farm funded the improvements of three ECD centres within the Raymond Mhlaba and Blue Crane Municipalities (EC). Both funders made use of Lima Rural Foundation as implementing agent using local artisans and subcontractors that earned them a very positive response from the community. PPT tracked construction progress on both these projects.

KZN COGTA was approached to assist with ECD awareness using local and provincial IDP platforms. The KZN MEC offered her full support and invited a presentation on ECD at the MUNIMEC meeting at the end of 2018. Click here for the MUNIMEC PowerPoint. PPT assisted COGTA with the assessment of all 53 IDP in 2018 to see to what extent IDPs provide for ECD. IDP ward documentation and COGTA IDP assessments were amended to provide for ECD as national priority programme.

Value added services such as awareness campaigns, training of practitioners, donation of educational equipment, and food via Jam were organised by Assupol Community Trust for the 40 ECD centres prioritised for improvements in Msinga and Nquthu and by Cookhouse Wind Farm for the 29 ECD centres surveyed in the Raymond Mhlaba and Blue Crane municipalities. PPT also arranged a few short course training modules via the National Development Agency (NDA) for all unfunded ECD centres prioritised for centre improvements and food for children via Lunch Box where required. Click here to view a tabular summary of ECD survey and infrastructure related projects.

The Department of Social Development(DSD), Department of Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs (COGTA), the South African Local Government Association (SALGA), Department of Health, Impande SA supported by the Nelson Mandela Foundation are working towards enhancing ECD in local government. Barriers to effective ECD provision on local government level and barriers to ECD partial care registration are addressed. PPT is assisting with the drafting of:

- An ECD Sector plan for inclusion in IDP

- A uniform ECD bylaw

- A document on Land use and land rights matters that creates a barrier to registration

- An ECD discussion document for SALGA

These documents are still in draft format and not yet ready to share.

The NMF made a video on land use issues as experienced by ECD centres in low income and informal settlement areas. Click here for a link to the Nelson Mandela Foundation video on bylaw and land use barriers experienced by ECD operators.

PPT developed a framework for the inclusion of ECD infrastructure within the National Housing Code. The aim was to enhance the current Socio Economic Amenities Programme by developing a sub programme that includes a policy, affordable standard designs for ECD centres, extensions, ablution facilities and jungle gyms, bills of quantities and technical guidelines. Building plans are ready for submission to municipalities and only require a site plan and the signoff of the foundation design by a structural engineer. This programme will enable municipalities to apply for funding for new ECD Centres as part of their normal IRDP housing or Informal Settlement Upgrading programmes. PPT worked with the support NGOs Lima Rural Foundation and Network Action Group (NAG) in developing the framework as well as a consultant (retired DHS Policy Director), Mr Louis van der Walt. The ECD Programme was presented by PPT at a National Policy Task Team meeting on 28 October 2020 and will be submitted to a Joint (DSD/DHS) Technical MINMEC meeting for approval.

Click on each item to open:

- Affordable ECD centre designs for 40 children with water borne sanitation (Type A) and for centres with free standing ablution facilities (Type B) including foundation and portal designs.

- Affordable new builds summary and cost estimate

- Design for 40 children (A201, Type A)

- Design foundation for 40 children (SA201, Type A)

- Design for 40 children (B201, Type B)

- Design foundation for 40 children (SB201, Type B)

- Design for ablution block for 40 children (B202, Type B)

- Sanitation Toddlers leaflet (Ilifa) 2018

The centre and foundation designs for 60, 80, 100 children can be obtained from PPT.

- Extension / component design – standalone classroom with veranda and standalone kitchen and admin block

- Design for standalone classroom (C101)

- Design foundation standalone classroom (SC101)

- Design for standalone kitchen – office (C201)

- Design foundation kitchen office (SC 201)

- Design for outdoor play equipment

PPT developed a Municipal ECD Guide based on the learning and experience gained by research and piloting the programmatic ECD response model.

The purpose of this guide is to:

- enable local municipalities and metros in South Africa, working closely with the Departments of Social Development (DSD), Basic Education (DBE) and Cooperative Government and Traditional Affairs(COGTA) and other stakeholders, to conduct improved planning, and to co-ordinate and utilise resource utilisation for ECD services.

- Provide a practical, programmatic framework for improving the access to and quality of ECD services in the municipality, especially within under-serviced, low-income communities.

- Enable the municipality to optimise its developmental role in ECD, especially in terms of improved planning, coordination and infrastructure provision.

- Enable improved and more efficient resource utilisation for improving ECD infrastructure.

- Encourage municipalities to rationalize and optimize their properties and facilities such as halls and community centres for the rendering of both centre and non-centre based ECD services

- Enable improved communication, coordination and institutional arrangements amongst key stakeholders involved in ECD (governmental, non-governmental and private sector).

- Highlight the need for increased operational funding and oversight to ensure regular preventative maintenance.

- Unlock improvements in ECD service provision at scale.

Click here to open the Municipal Guide for Early Childhood Development (ECD) Planning and Infrastructure Support. Specific annexures can be obtained from PPT upon request.

PPT made inputs during the initial stages of the development of the ECD Registration Framework that provides much-needed flexibilities and thereby enabling ECD centres in underserviced areas to obtain conditional registration. The ECD Registration Framework specifies the acceptable norms and standards for each level of registration in terms of environmental health and childcare matters.

PPT, appointed by the Network Action Group(NAG) in 2018, successfully completed the piloting of the ECD Registration Framework (gold, silver and bronze levels) at 15 unregistered ECD Centres in eThekwini (North) at the end of 2018. The pilot involved testing a standardised registration framework across different modes of ECD service delivery as well as in different geographical and economic contexts to assess its suitability for the intended purpose. The ECD Registration Framework (gold silver and bronze) was approved in August 2019 by the DSD and organised a workshop with the Department of Health and Environmental Health Practitioners at the end of 2020.

The ECD Registration Framework is central to the Vangasali Campaign for centre registration launched in 2020 that will enable the conditional registration and inclusion of many centres s in the government system of support.

PPT designed a comprehensive ECD survey template (160 questions and 335 data fields) in collaboration with eThekwini Metro, Environmental Health Practitioners (EHPs), DSD, UKZN, TREE, NAG (now Impande) Ilifa Labantwana and Assupol Community Trust. The survey covers questions on locational, institutional, governance, capacity of staff, administration, fees, health and safety threats, children, ECD programme, nutrition, ownership. distance to ECD centre, site, services, building conditions, outdoor play space and equipment and planned improvements by the ECD centre. Click here for copy of the survey form.

PPT surveyed 1,114 ECD centres attended by 41,419 children between 2015 and 2019. Of the 1,114 ECD centres, 457 ECD centres were located in 7 Local Municipalities (5 in KZN and 2 in EC) catering for 16,623 children, while 657 ECD centres were located in eThekwini Metro, KZN catering for 24,796 children.

The survey findings indicated that almost a third (31%) of the ECD centres were unknown to DSD and EHPs. More than half (57%) of the centres were NPO registered. Only 36% of these centres had partial care registration and only 25% of the centres received per child subsidies, while 88% of the 1,114 centres reported infrastructure deficits.

Click here for the Amaoti survey report.

Click here the Msinga and Nquthu Audit Report.

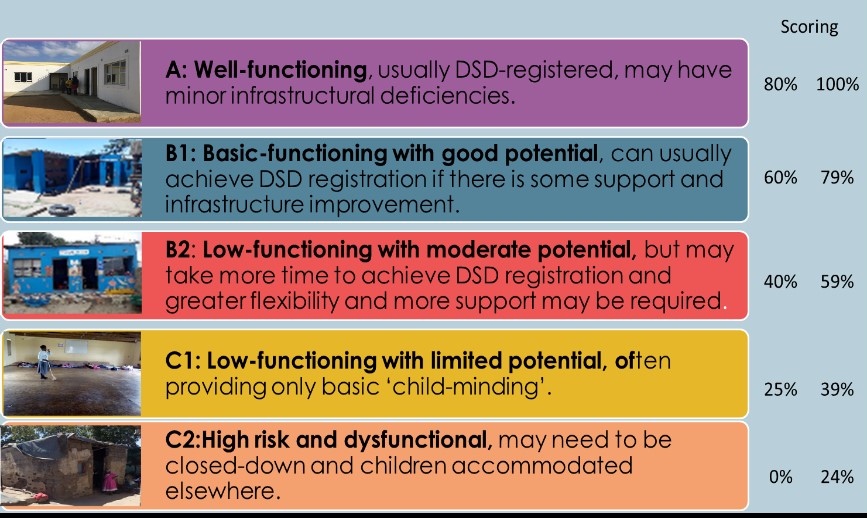

In 2016/17 PPT developed a framework for the categorisation of ECD centres based on their level of functionality and infrastructure and making use of data collected via ECD filed surveys. PPT also developed a related potential rating to assist with prioritising centres for infrastructure improvements.

This is a systematic framework in terms of which all ECD centres in a particular area (including unregistered, ‘less-formal’ centres) are identified (e.g. via a rapid field survey) and then categorised (based on an assessment of data collected) so as to better understand the status of ECD services provision in the area and to determine the types of support which may be appropriate.

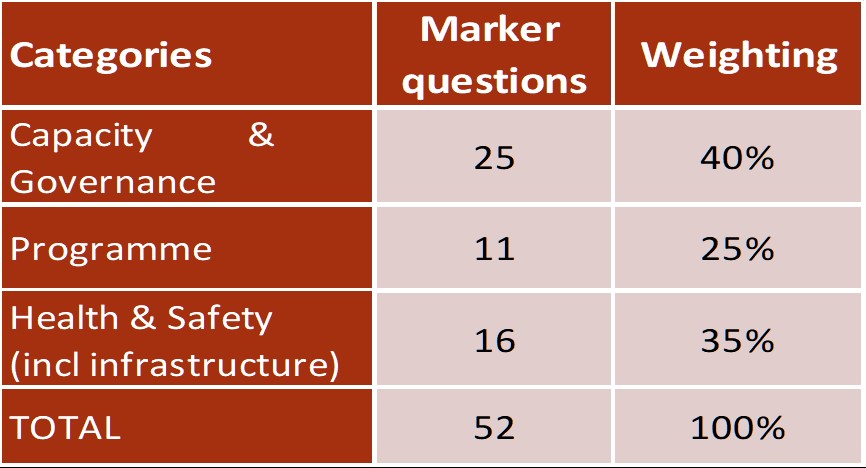

The categorisation framework makes use of 52 characteristics using information derived from the ECD survey. The 52 key marker questions/data fields are in three categories which relate to: capacity and governance; ECD programme and infrastructure; health and safety. Together these enable a determination of the level of functionality, potential, infrastructure adequacy and investment potential.

Given that the need is likely to exceed available infrastructure funding, there needs to be an agreed process of rational prioritisation in order to maximise limited financial and other resources and to ensure a more evidence based, depoliticized and accountable way of selecting ECD centres for state support.

Based on PPT’s survey and categorisation of 1085 ECD centres in eThekwini and 5 rural municipalities in KZN, and 29 ECD centres in 2 municipalities in the Eastern Cape, it emerged that typically more than half of all centres have the potential to provide acceptable ECD services if they received support i.e. centres in the categories A, B1 and B2.

Click here for more information on the ECD centre categorisation framework.

PPT developed and piloted a prioritisation method/system as part of its programmatic ECD response model. ECD data (derived from field surveys) and related categorisations are used to screen, shortlist and select centres for further assessment, response planning and support. This provides an effective method for allocating limited fiscal and other resources which is more evidence-based and equitable. It also removes possible bias in selecting centres and ensures that all existing centres are considered (and not only those on existing, limited databases of government). This fosters a fairer and more accountable selection process.

Shortlisting and selection enables more effective population-based ECD response planning and associated budgeting. Support to ECD centres would typically be done on a phased basis depending on available budget and other resources. Typically, those centres with the greatest potential and return on investment (using criteria as described below) would be selected first. This method would be used in order to achieve population based ECD response planning and the development of ‘bankable’ ECD improvement pipelines with associated budgets linked to Municipal and/or DSD MTEF or BEPP budgets.

A two phased shortlisting and prioritisation process was followed in all pilot municipalities:

- Shortlisting done by filtering the ECD database according to pre agreed criteria e.g. centre potential / DSD support, size / number of children who will benefit e.g. 20 +, years in operation e.g. 5 +, etc.) in terms of the registration status.

- Selection of priority centres from the shortlist. This is usually done by means of a workshop-attended by DSD personnel (social workers and service office managers), municipal personnel (environmental health practitioners (EHPs) and potentially those involved in social cluster/human settlements/IDP budgeting) and project team (who undertook the survey).

For more information: Click here for the PSPPD ECD Action Research Synthesis report (refer to section 4.4) or click here for the Municipal Guide for Early Childhood Development (ECD) Planning and Infrastructure Support (refer to 5.10).

Problems with infrastructure at ECD centres are the main barrier to them achieving registration and obtaining related ECD per child subsidies from the DSD. This means that ECD centres remain outside of the system of state oversight and support. Infrastructure problems also often pose significant health and safety threats to young children (e.g. inadequate sanitation, insufficient space, poor ventilation, lack of fencing etc.). Based on a survey of 1,114 ECD centres, 88% had infrastructure deficits. In rural areas the biggest problems related to basic services (water, sanitation, electricity) where only 48% met basic requirements, whereas in urban and metro environments, the biggest problems related to accommodation (e.g. not enough playrooms, no separate food preparation area, no sickbay) with only 34% meeting basic requirements and site matters (no playground, no or only partial fencing, no outdoor play equipment) where only 37% met the basic requirements.

Addressing ECD infrastructure in a programmatic, effective and cost-efficient fashion is thus a national priority.

It is noted that the main developmental role that the municipality can play is to support, plan for and fund improved ECD infrastructure, working with the DSD, ECD NPOs, support NGOs and other stakeholders (in addition to its regulatory role relating to environmental health and its role in ECD planning at municipal level).

Usually the municipality and DSD would need to prioritise those centres and operators which are suitable for state investment (not all centres are). This means identifying those centres/operators who have the potential to provide acceptable ECD services and which, either already have registration as a partial care facility or can achieve it if they receive improved infrastructure. Typically, the nominated / appointed technical person, DSD social workers and municipal EHPs would visit centres with potential and identify the infrastructure improvements which are most important in order to: a) mitigate health and safety threats; b) achieve conditional registration as a partial care facility preferably at silver level).

Improvement plans and cost estimates should be done for prioritised ECD centres on an annual basis to assist the municipalities to plan and budget for ECD infrastructure improvements and new builds to be implemented in the following financial year. This needs to be reflected in the IDP. Click here to read more in the Municipal Guide for Early Childhood Development (ECD) Planning and Infrastructure Support.

PPT undertook infrastructure assessments at 112 ECD centres rendering ECD services to 5,692 children in 2016/17. Infrastructure assessments were arranged with municipal EHPs and DSD social workers, in close consultation with the ECD operator / committee members to allow an opportunity for them to raise their infrastructure, health and safety issues and point out latent defects that may not otherwise be easily detected (e.g. roof leaks due to short overlap of corrugated iron roof sheets). EHPs must agree with the schedule of work to ensure that the ECD centre will be able to meet the requirements for silver level conditional registration. PPT developed a cost rate tool tested by Lima Rural Foundation to assist with the cost estimates.

Click below for:

- Potential scope of work for ECD infrastructural improvements

- Overview of ECD infrastructure response typologies

- Summary of estimates for the pilot projects (2017)

- Technical assessment for infrastructure improvements: Issues for consideration

- Summary of proposed ECD improvements used in funding request to Council, 2017

- Case study Khulisisiwe Umlazi

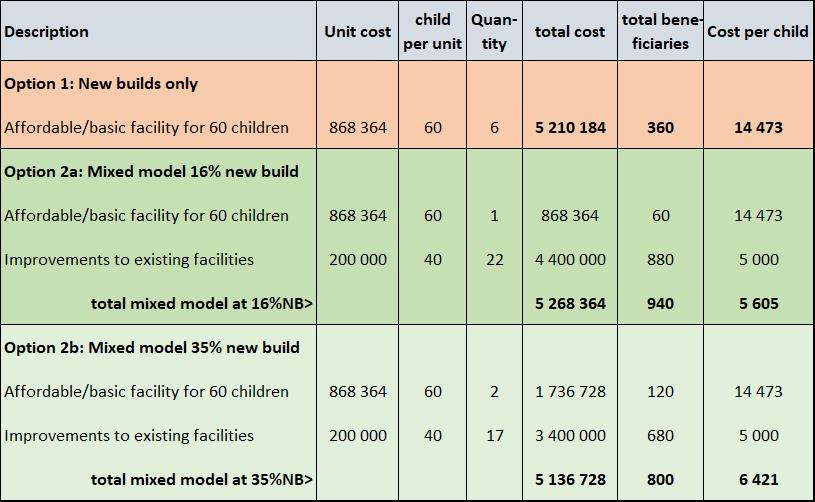

The main infrastructure focus needs to be on improving existing facilities wherever possible in order to achieve maximum impact/population coverage relative to capital investment. The cost of new facilities far exceeds the cost of improving existing facilities. 4-6 times more children can be assisted through infrastructure improvements to existing centres compared to new builds as illustrated in the table below. [4-5 times higher if the affordable new-build costs and specifications developed in 2020 are utilised and 6 times if the more expensive new-build models of the DSD are utilised dating back to 2017 which were at a significantly higher than necessary cost and specification.]

Cost-benefit:

One new build for 60 children = 4-5 improved centres for between 160 and 200 children

Optimal delivery mix:

15%-25% new build with balance on improvements

Delivery coverage:

R5.2 million can deliver 2 new builds and 17 improved facilities benefiting 800 children.

Prioritising improvements to existing facilities is important in order to move to scale in a programmatic fashion, maximise population coverage using limited fiscal and other resources and thereby achieve the national policy objective of ‘massification’ of ECD services. This means that there needs to be an appropriate mix of investment in improvements versus new builds. An appropriate mix will typically be 15% to 25% of budget expenditure on new builds with the balance on improvements to existing facilities. The municipality, working with the DSD and other stakeholders, will need to decide on the appropriate mix for its local context taking into consideration the factors outlined below:

- The prevalence and potential of existing facilities (registered and unregistered);

- The overall services backlog in particular local areas/wards;

- Prevailing land ownership and land use patterns;

- Total available capital funding for infrastructure;

- The availability of NPOs or other ECD operators who can effectively manage facilities and deliver acceptable ECD services.

Existing ECD centres prove demand for ECD services in that particular area. Existing ECD centres are also typically well located and accessible to parent households. One should also appreciate the fact the commitment of these ECD operators that persevere despite an often unsupportive environment. Focus groups consulted in Amaoti confirmed the importance of community based ECD centres not just as centres of educational value but also because they play such a strong support role within poor communities.

Infrastructure improvement requirements and costs will vary significantly from one centre to another. Fixed ‘packages’ are not viable. However, the types of infrastructure improvements can readily be grouped as follows, noting that they usually overlap (e.g. basic improvements with a building extension):

- Basic/minor improvements (building and services) – normal

- Description: These are required at most centres and are the top priority. They will typically include improvements to the building (e.g. roofing, windows etc.) and/or the services (e.g. toilets or fencing) or outdoor play equipment.

- Investment value: Typically, R50,000 to R200,000. Cost per child will typically average R2,500.

- Major improvements and extensions

- Description: As above, but to a higher level of investment and also including extensions typically for new kitchens, playrooms or ablution blocks.

- Investment value: Typically, R200,000 to R400,000. Extensions on their own typically R200,000 to R250,000 & R85,000 to R130,000 for stand-alone ablution facilities. A typical edu-tainer costs R577,300 for 25 children to R1,2 million for 55 children depending on size, finishes, etc.

- Emergency mitigations only

- Description: Only last resort – the provision only of basic/emergency mitigations to address serious health and safety issues (mostly relating to basic water and sanitation, fencing or minor building repairs).

- Investment value: Typically, R25,000 to R100,000

Click here for more information contained in the Municipal ECD Guide regarding ECD infrastructure options and approach (section 6.3)

Standard, affordable modular designs which are norms and standards compliant were prepared for four different sized new builds catering for 40, 60, 80 and 100 children in close collaboration with Lima Rural Foundation, Ilifa Labantwana, DSD, EHPs, NAG (now Impande SA) and other stakeholders. These designs cater for two types of sanitation solutions. This means that there are effectively eight different ECD centre designs – four for use in rural/ informal settlement areas with a free standing ablution facilities, and four for use in urban areas with internal flush toilets. Provision was also made for designs for extensions/ components such as a free standing playroom with a veranda and kitchen cum admin block. These designs have been approved by DSD and DHS for inclusion in the DHS Housing Code.

The designs make use of a standard steel frame structure and raft foundations to ensure structural integrity, irrespective of local conditions. They are cost-effective, meet the norms and standards required for ECD facilities, and make use of materials which are generally available from local hardware or building supply stores, both for the construction phase as well as for maintenance purposes. Standard raft foundations suitable for H2 soil conditions are utilised to limit problems for maintenance as well as cracking walls. The design creates a strong roof which cannot easily be blown off or otherwise damaged. All centres are plastered and painted. All centres are provided with aprons to keep water away from the foundations.

The standard typologies include: floor plans, elevation drawings, reinforced foundation and portal designs, energy efficiency calculations and construction notes. The standard plans are in a format which renders them ready for submission for building plan approval. The only additional requirements will be the sign-off by an engineer on the foundation design and a site plan by a draftsperson. There are also two designs for jungle gyms. All plans are available free of charge.

The cost of new builds ranges from R706 525 for a centre for 40 children that works out at R17 663 per child to R1 415 488 for 100 children that works out at R14 154 per child. Standard extensions for a kitchen cum office block amounts to R308 107 and a free standing ECD playroom with a veranda to R290 309.

This programme brought about a positive change in government’s design and specification philosophies to optimise limited funding providing maximum access to affordable ECD centres. Funding has been allocated by the DSD to provinces for the construction of affordable new builds.

Click on each item to open:

- Affordable ECD centre designs for 40 children with water borne sanitation (Type A) and for centres with free standing ablution facilities (Type B) including foundation and portal designs.

- Affordable new builds summary and cost estimate

- Design for 40 children (A201, Type A)

- Design foundation for 40 children (SA201, Type A)

- Design for 40 children (B201, Type B)

- Design foundation for 40 children (SB201, Type B)

- Design for ablution block for 40 children (B202, Type B)

- Sanitation Toddlers leaflet (Ilifa) 2018

The centre and foundation designs for 60, 80, 100 children can be obtained from PPT.

- Extension / component design – standalone classroom with veranda and standalone kitchen and admin block

- Design for standalone classroom (C101)

- Design foundation standalone classroom (SC101)

- Design for standalone kitchen – office (C201)

- Design foundation kitchen office (SC 201)

- Design for outdoor play equipment

- A case study Khulisisiwe Umlazi (2019)

- Affordable new builds summary and cost estimate

- Amaoti survey report (2016)

- Close out report – Phase 1 Msinga and Nquthu infrastructure improvement

- Cost breakdown : affordable modular ECD new builds and Standalone units/ extensions

- Costing of centres – per investment level per municipality (2017)

- Design for 40 children (A201, Type A)

- Design for 40 children (B201, Type B)

- Design for ablution block for 40 children (B202, Type B)

- Design for standalone classroom (C101)

- Design for standalone kitchen – office (C201)

- Design foundation for 40 children (SA201, Type A)

- Design foundation for 40 children (SB201, Type B)

- Design foundation kitchen office (SC 201)

- Design foundation standalone classroom (SC101)

- Design outdoor equipment (Medium) JG M 001

- Design outdoor equipment (Small) JG S 001

- Diagrams of ECD programmatic response model

- ECD centre categorisation framework (2019)

- ECD centre design to meet the needs of children with various disabilities (2019)

- ECD policy brief (2017)

- ECD Survey form used by eThekwini (2019)

- eThekwini ECD Briefing PowerPoint (2020)

- eThekwini ECD Support Project

- Extract on norms and standards (2018)

- Funding Model Document

- Informal Settlements: Informal ECD centres, HDA (2014)

- Introduction to SEIS (presentation, 2017)

- Msinga and Nquthu Audit Report

- Municipal ECD Guide

- MUNIMEC PowerPoint (2018)

- Norms and Standards Document

- Overview of ECD infrastructure response typologies

- Photos of ECD centre improvements (2017-2019)

- Photos of new build centres (2017-2019)

- Potential scope of work for ECD infrastructural improvements

- PSPPD ECD Action Research Full Report (2017)

- PSPPD ECD Action Research Synthesis Report (2017)

- PSPPD Policy Presentation (2017)

- PSPPD Policy Presentation KZN Premiers Office (2017)

- Sanitation Toddlers leaflet (Ilifa) 2018

- SEIS infographic (2017)

- Strategic ECD Infrastructure Support Project

- Summary of estimates for the pilot projects (2017)

- Summary of new build cost estimates

- Summary of proposed ECD improvements used in funding request to Council (2017)

- Tabular summary of ECD survey and infrastructure related projects (2015-2020)

- Technical assessment for infrastructure improvements: Issues for consideration